When a Publication Gets Personal

Billionaire Richard Branson calls his dyslexia a superpower. He’s been challenging anyone paying attention to shift the narrative from shame to bold celebration of what is possible when people think differently. There is a school in Massachusetts that has known that since its founding. As my team worked with them on a new publication, my personal narrative shifted as well, changing my perspective on the past, present and future.

We can aim for work-life balance. But work-life blending is an unexpected grace.

Carroll School exists to empower children with language-based learning difficulties, including dyslexia, to leverage their assets and move us all closer to a day when being dyslexic is not only celebrated but even highlighted on professional resumes.

As we approached writing and designing a signature stewardship piece we had a learning curve with a new client. The schedule and budget were tight. We had an amazing anchor story about the largest bequest in the school’s history, but a clear directive to produce a piece with a level playing field where all donors would feel equally acknowledged. That directive came directly from the head of school who wanted every aspect of the piece to be infused with gratitude.

On the plus side, we had some great ideas for stories and images from students, parents and educators. Dyslexia, we learned, runs in families. We had to think about our audience through a lens that was unfamiliar to us. We learned to shorten our sentences and headlines. The point size on pull-quotes went up. We needed to say less with more — more white space, in particular.

For us, there were eye-opening facts we had to consider:

At least 1 in 5 students in every classroom in every school in America is dyslexic. If your kid is in a classroom with 20, chances are 4 of them are dyslexic or struggle with language-based difficulties. That’s true whether or not these issues have been identified or the teacher is trained to help. Do the math. No, don’t. Keep reading.

There are tools that make a big difference. We learned about Orton-Gillingham, a highly structured approach to reading and spelling that breaks learning into small units involving letters and sounds. Every student builds on what he or she has learned, over time, solving what was once a puzzle. No two students solve the puzzle at exactly the same pace.

We learned from alumni how they still relied upon the strategies they learned at Carroll and how that experience of competence and confidence changed their lives.

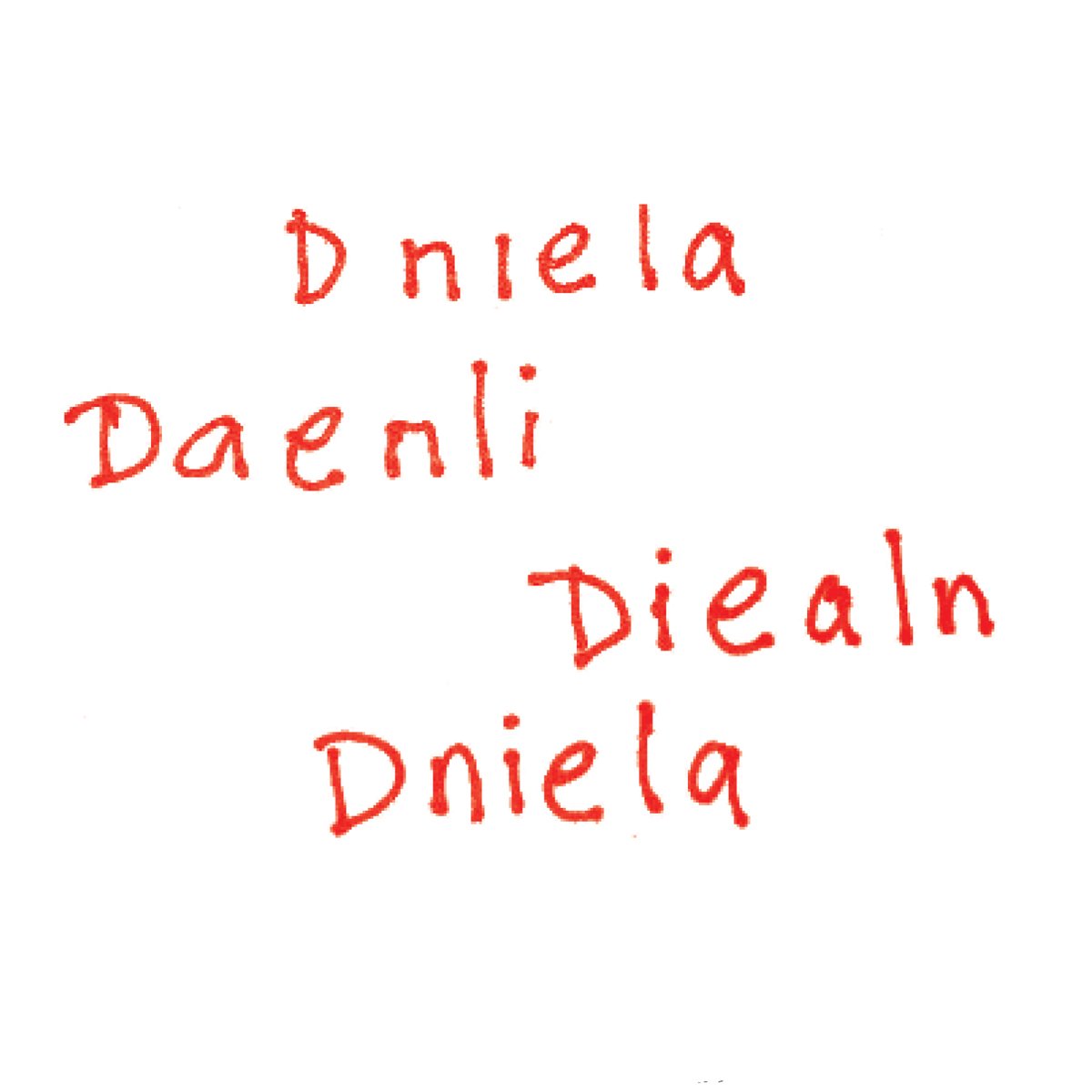

We learned about a mother watching her second-grade son sign Valentine cards at the kitchen able who noticed he spelled his name a different way each time. He had the right letters, just in a different order. Daniel mastered the skills he needed at Carroll to earn an undergraduate degree in engineering. He is pursuing his MBA. His parents are leadership-level volunteers who give insight and hope to others gained through their experience.

We met John Walton, a fourth-grade teacher who was once “that kid” pulled out of the classroom for extra help. Luckily, he was the son of a teacher who recognized the support he needed to harness his superpower, which he now shares with his students.

Throughout the work, I thought about Bobby, my oldest brother, born in 1957. As we helped celebrate the lives that are changed at the Carroll School, I understood a little more about the pain dyslexia caused him and my parents. He did not have the benefit of a life-affirming, empowering place like the Carroll School.

We spent Christmas Eve together in 1997, a week before he died. I made pot roast that night. I was irritated that he was late because he needed to help me assemble the bike for Francesca and the telescope for Kelly. My daughters were happy that Uncle Bobby would be with us that Christmas morning. I asked him to write the note from Santa so they wouldn’t recognize my writing. It had spelling errors. I told the kids it must have been from one of the elves.

That morning was the last time we saw him.

Bobby fell down a flight of cement stairs in my sister’s basement on New Year's Eve. He’d been drinking that night. By the time he was an adult, he drank too much. It was bitterly cold so he went down to the basement for a smoke to keep it away from my sister’s baby, Mary, his fifth niece, who had been named for both grandmothers. He got to hold her that night, but he never got the cigarette. He also never woke up. He was 39.

Left to right: Bobby with Anne, as a young man, at far right with his aunt and uncle.

The team at Mass General gave his heart to someone named Michael who married the ICU nurse who took care of him. We were all invited to the wedding. My mother danced with his heart when the DJ said, “And now the groom would like to dance with the other mother who gave him life.”

Before Mom died in 2018, she told me how much she wished she knew more about dyslexia back then. “I just wish I could apologize to him for not having done more. We moved so many times.” I kidded Mom that Bobby was her favorite. She said that wasn’t true while wiping a tear, but it was.

“He never talked back. He was so polite. At least I’m not worrying about him anymore.”

Dyslexia did not kill my brother. However, it wasn’t his superpower. It was a confidence-killer. It was a secret that made everything harder. He struggled all the way through school. Grades were always a source of embarrassment. Even so, it was clear that he enjoyed deep conversations about theology, philosophy, science, art and the humanities. He won ribbons at the art fairs at St. Bridget’s School and taught himself to play the guitar. He was kind and humble and loved by many.

As he watched friends heading off to college, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. He handled the realities of boot camp at Parris Island without a complaint. He never complained, including the fact that he didn’t understand everything on the boards of his childhood classrooms. He was like that, very polite. He is buried next to our great grandmother, Agnes. She loved him, too.

Bobby never had children of his own, but if he had, there’s a possibility they might have been dyslexic. I know now it runs in families. I understand now how it affects family histories.

At least 1 in 5 kids in every classroom is dyslexic. He was that one.

I’m so grateful that some of them are at Carroll.